3. Fort Pans

The third chapter considers what I call the Fort Pans, which are small handled bowls that name forts along Hadrian's Wall in England. Some of the pans are decorated with a fortified wall motif common in Roman art, but one is ornamented with triskel motifs (spinning triangles) common in Celtic art. This is the chapter where I dig into the cultural complexities of commemorating an imperial frontier.

Key Artifacts (and Replicas)

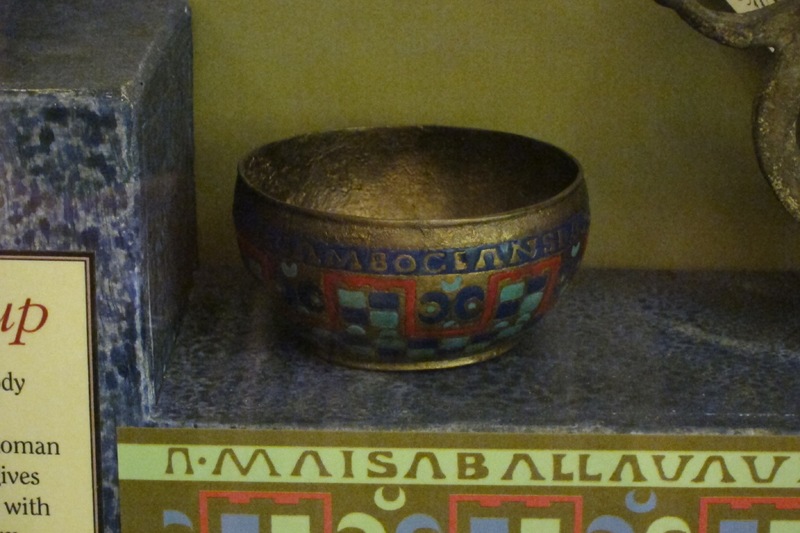

The Amiens Patera, Rudge Cup, and Ilam Pan must have been stunning when their metal was gleaming, their enamel vibrantly colorful, and their handles still attached, but each has suffered damage over time. The Amiens Patera is still intact, but its surface has deteriorated. The Rudge Cup has lost is handle and most of its enameling. The Ilam Pan has also lost its handle and its enamel has partly faded.

At Alnwick Castle in northern England, the Rudge Cup is displayed next to a replica with colorful enameling restored. (Regrettably, the Rudge Cup did not feature in the scenes from Harry Potter and Downtown Abbey filmed elsewhere at the castle, though I could imagine some relevant story lines.)

The British Museum has a different replica of the Rudge Cup, one that reflects its current condition. It is on display in the Roman Britain gallery, often next to the museum's replica of the Ilam Pan. This latter replica was produced as a place-holder of sorts because the actual Ilam Pan circulates among three institutions: the British Museum, the Potteries Museum at Stoke-on-Trent, and the Tullie House Museum near Hadrian's Wall. I saw the ancient artifact at the Potteries Museum.

The Bath Patera and Hildburgh Fragment are not technically Fort Pans, because they do not name any forts. Yet they are usually brought into discussions of the series because they show variations on the encircling wall motif. The Bath Patera lost its enameling because it was tossed into the hot spring at Bath in antiquity. The Hildburgh Fragment has been thought to be lost over the years, but it is actually just in storage at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Enameling

The Getty Art and Architectural Thesaurus defines enameling as "The process of applying a vitreous coating to metal, ceramic, glass, or other surfaces by fusion using heat in a kiln or furnace, with the result of creating a smooth, hard surface."

Enameled metalwork was especially popular in the northern Roman provinces. One of the best examples is the West Lothian pan, where the enameling appears to flow across the surface. The Braughing Pan has a similarly fluid design, but has suffered more damage. The Bingen Bowl has a checkerboard pattern that shows how the metal has been divided into cells to hold the different colors of enamel. I wasn't able to illustrate these vessels in the book and am glad to do so here.

Enameling was also used to decorate jewelry, among other items. In the book, I illustrate two so-called dragonesque brooches with metamorphosing monsters (British Museum 1088.70a-b and POA.201).

Triskel Motifs

Triskels are triangles with extended, curving corners. In some versions, the triangle itself disappears and the motif becomes a dot with three radiating legs.

This motif was popular in the metalwork of Celtic peoples before they were conquered by Romans. Even after conquest, artists kept the motif alive by continuing to work with it. In the British Isles, the motif persisted through the Roman era and found new popularity in the metalwork and manuscripts produced during the Late Antique and Medieval eras. The Ilam Pan counts among the objects that kept the motif alive during the era of Roman rule.

In the book, I illustrate the Amfreville Helmet and Battersea Shield as pre-Roman examples of the motif. I mention the Book of Kells as a post-Roman example but wasn't able to illustrate it. Folio 34R of that book has especially beautiful triskels.

Wall motifs

Fortified walls were a popular motif in Roman art. In floor mosaics, the motif was used as a clever framing device: the motif runs around the edges of rooms just as actual walls run around forts and important cities. A good example is the mosaic at the Fishborne Palace in southern England (below). Crowns in the form of an encircling wall (so-called mural crowns) were awarded to soldiers for bravery. That is what you see on the side of a funerary altar dedicated to Quintus Sulpicius Celsus (below) and also integrated into the Ribchester helmet. Goddesses who protected cities were also depicted wearing mural crowns. In the book, I illustrate the dedication to Brigantia. A statue depicting the goddess Fortuna is another good example (below). On the Fort Pans, the motif glosses or helps visualize the forts listed around the vessel's rim.

Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS)

In England and Wales, the legal framework of the PAS allows metal detectorists and other enthusiasts to hunt for treasure as long as they report finds to a local liaison officer, who documents the artifacts in a public database. Finds of "national importance"—such as the Ilam Pan, which was discovered in this way—can be claimed and acquired by the state for public museums. This system has revolutionized understanding of metalwork from Roman Britain, and the data kept shifting even while I was writing. I like to tell my students that studying ancient art is like studying contemporary art: you never know what might emerge next.

PAS objects related to the book:

Ilam Pan (Fort Pan): WMID-3FE965

Basildon Fragment (Fort Pan): ESS-5945F8

Fob with Triskel: NMGW-6368D1

Disk Brooch with triskel and enamel: NMGW-474B78

Crowle Pan with triskels and enamel: FAKL-9900E3

Winterton Pan with checkerboard pattern and enamel: NLM-F50443

Eastrington Pan with checkerboard pattern, enamel, and handle: YORYM-20B68C

Hadrian's Wall and Forts

At Hadrian's Wall, I learned why many of the maps of the region are laminated: the weather is, shall we say, unpredictable. Yet the landscape is stunning and internationally popular for hikes.

In antiquity, this frontier was one of the great contact zones of the Roman Empire. The Roman wall stretching across the island here was never intended to be an impenetrable barrier, but instead opened at regular intervals so that circulation could be monitored and controlled. The wall cut across the territories of several Celtic peoples, many of whom maintained traditional ways of life. Nearby forts were guarded by soldiers from all over the empire, and they set up religious dedications and tombstones recording their names and origins. Many brought their families with them, as Elizabeth M. Greene has shown with research focused on Vindolanda, a fort that was near but not directly on the wall.

Highlights from my research trip included Arbeia, likewise near but not on the wall, as well as Chesters, which stood directly in the line of the wall. Neither is named on the Fort Pans, but Arbeia is famous as the findspot for the tombstones of Regina (a formerly enslaved Celtic woman married to a man from Syrian Palmyra) and Victor (a formerly enslaved Maurish man from North Africa loved by a man from Spain). Chesters is famous for being the fort that guarded the wall's crossing of the North Tyne river. You'll find related images on the Hadrian's Wall page, along with a view of a room-sized model of the wall and its forts on display at Newcastle, where a new segment of the wall was recently found.

Celts: Who were they?

The Celts are a slippery topic: popular perception and academic understanding differ greatly.

In the United States, many people associate the Celts especially with Ireland, a place where the Celtic language has survived and where Celtic crafts are still created (note that those Celtic knots actually owe a lot to the designs of the Anglo-Saxons, another misunderstood group).

Specialists will tell you that Celtic peoples once inhabited much of Europe. In this sense, Gauls and Galatians are included among Celtic peoples. Yet specialists also insist that we use the term "Celtic" carefully, because the ancient communities in question did not perceive themselves to be a unified people or nation. Consider the complexities of the terms "American," "Asian," and "African," and you'll have some sense of the difficulties also posed by the term "Celtic."

To learn more, I recommend an exhibit called Celts: Art and Identity, organized by the British Museum and the National Museums of Scotland. Curator Julia Farley has an insightful blog post that starts with the Greek and Roman perceptions of Celts that continue to shape modern biases. The exhibition catalog is gorgeous and presents up-to-date research.

Bonus: Backstory

My interest in souvenirs began with this chapter on the Fort Pans. I was conducting research for a book about the impact of empire on Celtic art and got hooked on the Ilam Pan. At the time, there were few publications on Roman souvenirs, aside from Ernst Künzl's pioneering work in German. The more I looked at the Ilam Pan, Rudge Cup, and Amiens Patera, the more I wanted to compare them to other portrayals of place. So I set aside the Celtic book and shifted my focus to the objects that would help me understand how places came to be known and visualized on the Roman Empire's portable art.

Stay tuned: I still plan to write that Celtic book!