4. Bay Bottles

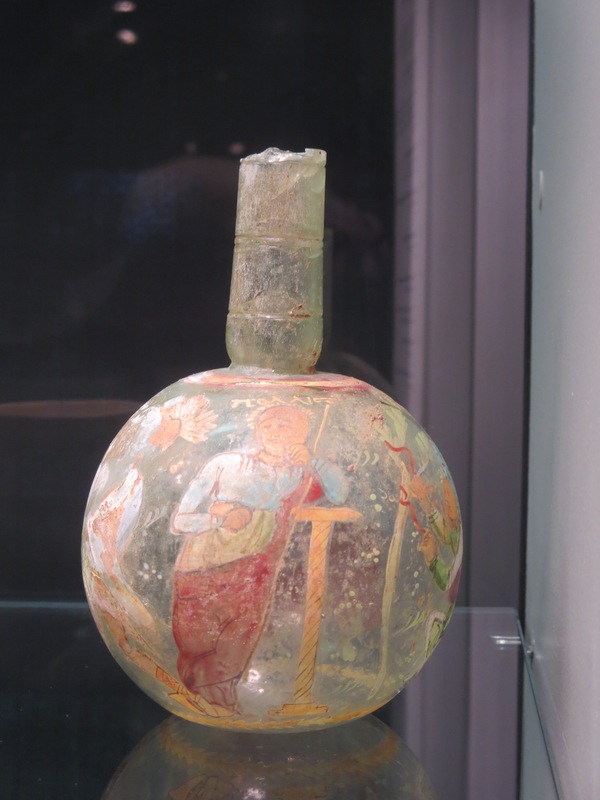

The fourth chapter addresses what I call the Bay Bottles, which were decorated with labeled scenes of Baia and Pozzuoli around 300 CE. These are the most complex views of places to survive on Roman vessels, and they offer insight into the fame and fascination of these two cities along the northern shore of the Bay of Naples.

Key Artifacts

Each bottle has a unique hand-drawn design, and those designs draw on a shared repertoire of urban features. Reconstruction drawings (coming soon!) make them easier to compare and also show the full series. I illustrate three of the bottles in color below.

Key Destinations

Baia (Baiae) and Pozzuoli (Puteoli) had opposite reputations in antiquity. Baia was a resort spa, where the famous and fabulous went to restore themselves and have a good time. Pozzuoli was one of the empire's major ports, with a full complement of urban amenities. These cities stood opposite each other on an inlet of the northern Bay of Naples: when you were in one place, you could see the other. You could also see glimpses of these places on the Bay Bottles that circulated to destinations in Italy (Ostia and Populonia), Spain (Mérida and Astorga), and Germany (Köln). This circulation helps us understand the global experience of the Roman Empire, where you could be in one place while thinking about another far way.

The following places have Destinations pages on this site: Baia | Pozzuoli | Ostia | Mérida | Köln

Comparanda: Glass

In the book, I compare the Bay Bottles to three different types of contemporaneous glassware. I look first at bottles of the same shape decorated with subjects ranging from charioteers to myths. Below, I show one bottle with a charioteer and his horses and another with the myth of Apollo and Marsyas. One has the design abraded into the surface; the other has colorful enameling. I wasn't able to illustrate either of these in book, so am glad to show this comparison here. They help us see the other subjects that craftmen thought would work well on a bottle's curved surface.

I also look at cage cups, otherwise known as vasa diatreta or open work vessels. In the book, I illustrate the cage cup from Köln (shown below) and mention one in Milan. As is typical for this medium, each has a flexible phrase exhorting the viewer to drink and live long and well. The cage cups help us see the attention craftsmen gave to designing text. They also demonstrate a trend: such wishes also adorn other glassware, including most of the Bay Bottles, where the phrases can be found around the tops of the scenes.

In so-called "gold glass," designs are often made with gold threads or foil, sealed between disks, and embedded in plates and bowls. Wishes also occur in this medium, and a broad range of subjects find representation. A good place to learn more is the "Catalogue of Late Antique Gold Glass at the British Museum" (hint: the museum's webpage for this book has a "related objects" tab with helpful links).

As I discuss in the book, a few fragments indicate that places could be depicted in all of these types of glassware, but the Bay Bottles remain distinct in being a multi-vessel series focused repeatedly on the same cities.

Motifs: Women with Cups

Among the Bay Bottles, both the Warsaw vessel and the Astorga fragment represent a woman turning and holding a cup. This figure may personify Baia (i.e. represent the place in human form) or alternatively represent a nymph for whom Baia was named. Piero Gianfrotta has helpfully connected this figure to a pose that was popular in a range of media, from fresco paintings and mosaics to glass bottles and cups. One of the most fascinating is the glass cup at the British Museum (illustrated to the left), which I mention in an endnote but do not illustrate in the book. The cup represents a man carving a stone to measure the Nile River. The scene also includes a building and a turning female figure (perhaps here the goddess Isis due to the sistrum or rattle that she holds). Such comparisons help us see how the Bay Bottles fit into the empire's broader visual culture.

Motifs: Harbors and Ports

Harbors and ports were such popular subjects in Roman art that it can sometimes be difficult to tell when a particular place is being represented and when a type of place is being evoked. This is the case for a small fresco painting from the Bay of Naples illustrated to the left. It may evoke Pozzuoli, the most important port on the bay, or it may not. What is remarkable about scenes of Pozzuoli on the Bay Bottles is their labeling: several name Pozzuoli directly so that viewers don't have to wonder.

Links to other views of ports illustrated in the book:

Torlonia Collection: Relief sculpture representing Ostia/Portus

Vatican Collection: Sarcophagus representing a port, perhaps Ostia/Portus

Getty Museum: Lamps (83.AQ.438.248 and 83.AQ.438.249) representing a port, perhaps Carthage

Motifs: Architecture on Coins

Coins circulated images of places, but only certain cities were visualized in this way. These architectural motifs have been well-studied by Nathan Elkins, among others, with attention both to identification and to strategies for reducing massive buildings to tiny views. Digital databases such as the Online Coins of the Roman Empire make this evidence increasingly easy to find.

Here are links to selected coins related to the chapter (RIC = Roman Imperial Coinage, a series of reference catalogs):

Mérida Gateway: RIC I (second edition), Augustus 9A | 9B | 10 | 11A. Mérida, a provincial capital, was visualized by its gateway.

Ostia/Portus Harbor: RIC 1 (second edition), Nero 178 | 179 | 181 | 182 | 440 | 441 and RIC 2, Trajan 631. The coins commemorating the major harbor at Ostia/Portus make an interesting comparison to the images of Pozzuoli on the Bay Bottles.

Rome, Circus Maximus: RIC 2, Trajan 571. The coins commemorating Trajan's renovation of the Circus Maximus highlight the monuments on the central axis of the track in contrast to the representations of stadia (below), where the track is kept clear for track and field events.

Rome, Stadium of Domitian: RIC 4, Septimius Severus 260. Stadia were rare in the western provinces, which makes Pozzuoli's all the more interesting and helps explain why it was represented and labeled on the Bay Bottles.

Rome, Colosseum (Flavian Amphitheater): RIC 2.1 (second edition), Domitian 131. The coins commemorating the Colosseum reveal the visual strategy of showing a building as it looked from the ground and from the sky simultaneously, so that both the exterior and interior are visible. This same strategy is used for the spectacle buildings on the Bay Bottles.

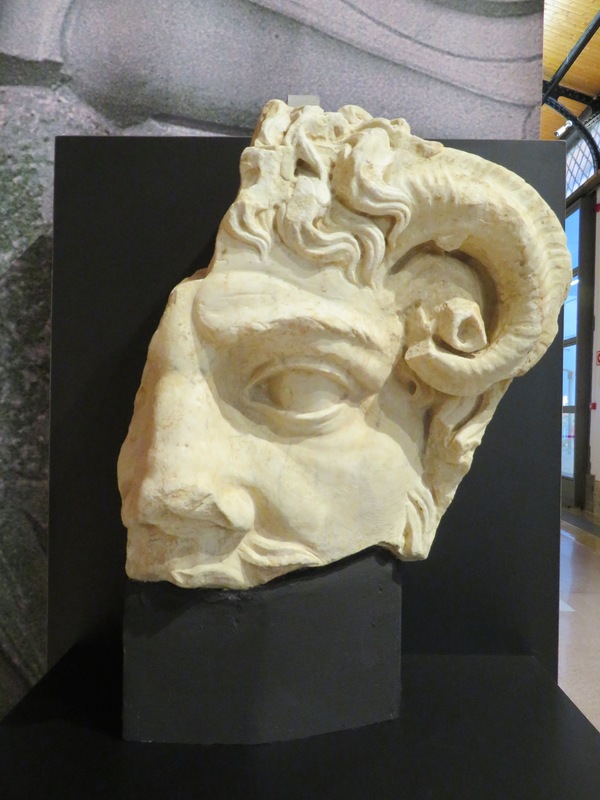

Connections and Omissions: Shields and Caryatids

I was surpised to realize that so many of this chapter's places had porticoes (covered walkways) with alternating caryatids (statues of women serving as columns) and shields (in this case, large medallions with faces at their centers). As Josephine Shaya has argued, the Forum of Augustus in Rome (below) set an important precedent for this feature, and variations survive at Pozzuoli, Mérida, and Tarragona. Eleri Cousins has suggested that the puzzling "medallion and face" on a temple pediment at Bath might also be related to this phenomenon. This design trend has been easy to overlook because of the fragmentary nature of the sculptures and the distance between sites. The ones from Pozzuoli do not appear on the Bay Bottles, which is a reminder of how selective these views really were.

Bonus: Places and Reputations

On my most recent visit to Rome's Crypta Balbi (aka the theater and portico of Lucius Cornelius Balbus the Younger from Cádiz, mentioned in Chapter 1), I noticed a panel describing and illustrating beautiful perforated vessels. These strainers were labeled with their craftsman's name and the phrase "fecit in Circo Flaminio," meaning made around the Circus Flaminius (which stood near the theater and portico).

I traced one of the vessels to the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. I mention it in the book's conclusion, because the phrase "fecit in circo flamino" highlights yet another way that a place's reputation could be made and spread through portable art. In this case, the reference to the Circus Flaminius was intended to evoke not the chariot racing we might expect at a circus, but rather the fine metalwork for which its neighborhood had become known.