2. Spectacle Cups

My second chapter looks closely at named charioteers and gladiators on glass cups that were popular around 75 CE. What is fascinating about these Spectacle Cups is that they are mold-blown. In this technique, relatively new at the time, craftsmen made a reusable mold, blew molten glass into it, and then "mass-produced" vessels with complex designs. (The Corning Museum of Glass has a good video of this process). This is the moment in Roman history when glass became an accesible luxury. I argue that glass craftsmen experimented with sports scenes as they were trying to find a niche in the market with a new take on a popular theme. I also look closely at the aesthetics of glass. The translucence (meaning you can see through it) allows imagery to be visible on both sides of the vessel wall, and that optical effect offered new viewing experiences of sports scenes (look at the Montagnole Cup below). The chapter also considers the places where these cups have been excavated, primarily in the northwest provinces, in order to understand what viewers would have known about the events and their architecture. London and Lyon count among these destinations. A key breakthrough for me came when I found modern replicas of the cups, which I could handle, scan and model in ways not possible for fragile ancient glass.

Key Artifacts

As you can see in the images below, the Spectacle Cups and Jars were produced in a striking range of colors. The image of the Montagnole Cup has the ideal viewing angle for this translucent glassware. This oblique angle lets you see most of the imagery all at once. Other well-preserved vessels addressed in the book include the Couvin Cup, the Chavagnes Cup, and the Mainz Cup.

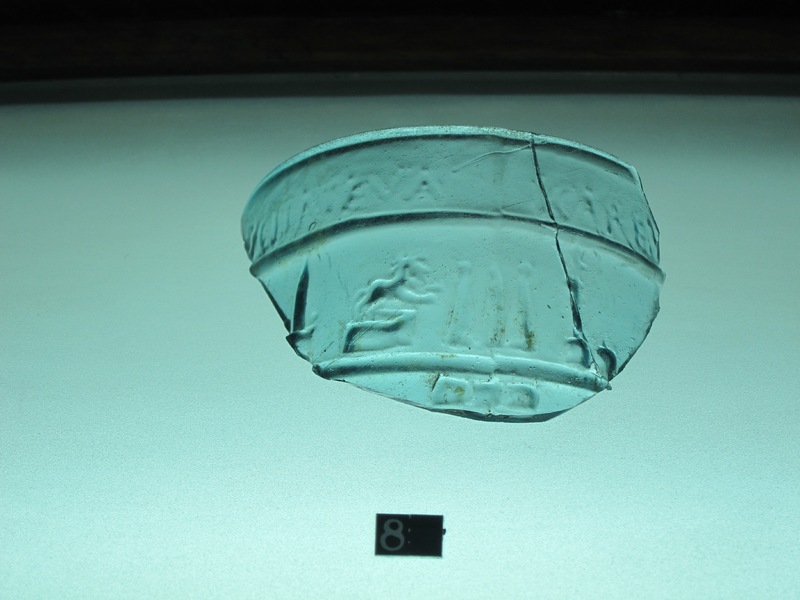

Bonus: Far Flung Fragments

Below are a few fragments that I came across in my travels, but did not have room to illustrate in the book. Track-and-field competitions are relatively rare on these vessels, so I was thrilled to see the so-called athlete fragment in London. I was also excited to find fragments from Nîmes and Ampurias, because both of those sites are on the Itinerary Cups that I address in Chapter 1. Glassware was something else these sites had in common.

Mold-Blown Glassware

The Spectacle Wares are unusual among mold-blown glass vessels because their designs combine words with scenes of people. Other series in this medium feature people without words, patterns alone, or words with patterns, as you can see in the bonus images below.

To learn more about this type of glass, I recommend Christopher Lightfoot's 2014 exhibition and book about Ennion, whose workshop pushed the boundaries of mold-blown design in the early first century CE. I was especially excited to find a mold-blown jar by Ennion at Cádiz, a city featured in Chapter 1. Ennion's vessels paved the way for the next generation of breakthroughs, including the Spectacle Wares.

If you want to do a deep dive into this medium, the following museums have strong collections online. I've picked out a few highlights to get you started. Unfortunately, most of the major examples come from the art market rather than controlled excavations, so it is difficult to know where they were made and found.

Metropolitan Museum: Ennion cup; knobbed cup; shell and dolphin cup; victory cup

Corning Museum: Ennion Cup; knobbed cup; be merry cup

Yale Art Gallery: Ennion bowl; myth cup

Gladiators and Charioteers in Art

Charioteers and gladiators were popular in a range of media, as you can see in the images below. The Spectacle Cups are special: when you hold one and look down at an angle, the contestants seem to be standing upright in a circle around your hand. In opaque media (terracotta, silver, stone, mosaics, etc.), you cannot see through the material so you only see the scene on one side of the object. In the book, I discuss the circus plaque and silver cup illustrated below. I don't focus on funerary mouments as much, but the bonus view of the Köln gladiator tombstone is a good example.

Below are links to other opaque artifacts that I had in mind while writing. Most are either illustrated in the book or cited in the endnotes.

Metropolitan Museum, New York: lamp with gladiatorial equipment; lamp with single gladiator; gladiator figurine.

British Museum, London: lamp with gladiatorial equipment; lamp with paired gladiators (also on Sketchfab).

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna: plaque depicting a wreck in the Circus Maximus

Antikensammlung Staatlichen Museen, Berlin: lamp showing monuments in the Circus Maximus; lamp showing the dolphin lap counter

Settings for Spectacles

Although the Spectacle Wares with gladiators do not show amphitheaters, those with charioteers use elements of circus architecture to organize the scenes and evoke the setting. I argue that this difference relates to the views from the stands: amphitheaters did not have permanent features on the arena floor, but circuses had a central barrier around which charioteers raced. Images from the first and second centuries CE reveal that the barrier at Rome's Circus Maximus had turning posts marking each end. In between stood lap counters, monuments, water features, and an obelisk from Egypt. In the early modern era, this so-called Flaminian obelisk was re-erected in Rome's Piazza del Popolo. (The so-called Lateran obelisk was added to the circus barrier around 350 CE and likewise later moved.)

Circuses and charioteers became popular subjects for floor mosaics in the second and third centures CE. These room-sized images are the largest representations of circus settings and are particularly helpful for seeing how elements of the central barriers were imagined. The mosaic from Barcelona below may represent the Circus Maximus. The one from Lyon shows a more general scene: notice the barriers at either end, the water feature, the counters measuring the seven laps of every race, and the obelisk that stood at the finish line (about midway down the track).

Chrysippus: Visionary Artist

In the book, I mention the ceramic artist Chrysippus, but I was was unable to illustrate his fascinating work. I'm glad to have a chance to highlight it here.

Chrysippus was active in and around Lyon at the end of the first century BCE, when this area of France had been part of the empire for a generation or two (with Caesar having conquered the region in the 50s BCE). Chrysippus' innovative designs for tall terrcotta goblets feature circus and gladiatorial scenes (among other themes). I argue that they offer important evidence for knowledge of these sports, even before the events and their architecture became common in the province. The Spectacle Cups, many if not most of which have been excavated in France, were therefore more novel for their glass material than their subject matter.

For reconstruction drawings of his goblets, see Armand Desbat, "L'atelier de gobelets d'Aco de Saint-Romain-en-Gal (Rhône)," Actes du congrès de Reims. 16 - 19 mai 1985, Marseille, Société française d'étude de la céramique antique en Gaule, Martine Genin, Armand Desbat, Sandrine Elaigne, Colette Laroche, and Bernard Dangréaux, “Les productions de l’atelier de la Muette,” Gallia 53 (1996): 41–191, especially plates 41–77 (online).

For photographs, the online catalog of Lyon's fantastic archaeological museum shows a cup with gladiators (2007.5.8) and many fragments with gladiators (2007.5.4; 2007.5.6; 2007.5.7).

Chrysippus is known to us today because he signed his work. You might just be able to see his signature on the mold illustrated below.

Charioteers and Gladiators on later Vessels

The Spectacle Cups ceased production around 100 CE for reasons that are still debated. Nonetheless, charioteers and gladiators continued to be popular subjects on other kinds of glass vessels. On these later examples, the imagery is primarily visible on the exterior of the vessel wall (rather than both sides, which is only possible with mold-blown cups). The cup and bottle below are bonus images to illustrate this point. The circus cup at the Metropolitan Museum is a good example, too.

Final Thoughts: True Souvenirs?

The Spectacle Wares record knowledge of popular sports stars on semi-luxurious commmodities. They are not souvenirs of particular events.

In contrast, Verdullus, a terracotta artist working in Spain, may be responsible for true souvenirs of spectacles. His bowls feature not only named contestants, but also the dates of particular events and the names of their sponsors. I mention these wares in the book's conclusion, but was not able to illustrate them. His work deserves to be better known.

For more about the circus wares of Verdullus, see Marc Mayer Olivé, “Propuesta de lectura para el vaso de los circienses del Alfar de la Maja,” Kalakorikos 3 (1998): 187–92 (online) and Juan Antonio Jiménez Sánchez, “Interpretación de vasos con motivos circenses procendentes de Calahorra,” Kalakorikos 8 (2003): 31–46 (online). For his gladiators, see Giulia Baratta, "I gladiatori di Gaius Valerius Verdullus," Archeologia Classica LXXI (2020): 189-220.